By DANIELLE FITZPATRICK

Florida is no stranger to rain. And while this year’s hurricane season ended without a storm making landfall in the Sunshine State, that doesn’t mean the threat of flooding has passed. As many residents know, just one heavy afternoon downpour, or several days of steady rain, can quickly lead to flooding.

That’s why flood protection is essential. But there’s no one-size-fits-all solution. Understanding how water moves through Florida’s landscape and working with nature, instead of against it, is key. Effective flood protection combines both natural and engineered approaches to manage water safely and sustainably.

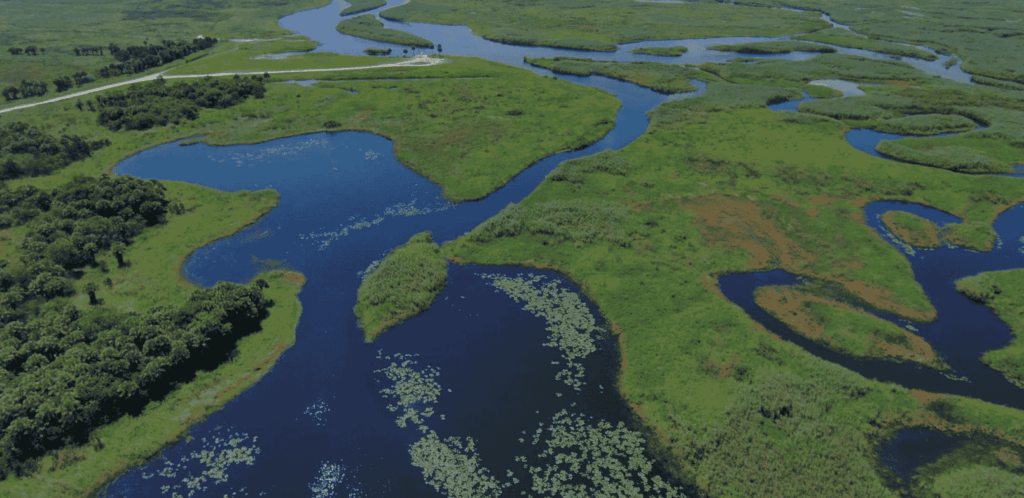

Florida’s environment provides some of the best natural protection against flooding. Wetlands and floodplains act like sponges, soaking up rainfall and slowing the movement of water across the landscape. Trees, shrubs and other wetland vegetation help disperse floodwaters, reducing their speed and force. That’s why the St. Johns River Water Management District actively pursues land purchases that conserve wetlands and floodplains. These natural systems allow water to move safely across the landscape, reducing flood risk for nearby communities.

“Water levels in natural systems rise and fall in response to the rainy and dry season,” said Cammie Dewey, Middle St. Johns River Strategic Planning Basin Coordinator. “Floodplains are an extension of that range, providing storage for additional volumes of water during large rain events or extended periods of rainfall during the rainy season.”

Across the District, more than 775,000 acres of land are preserved and managed, including extensive floodplain wetlands along the St. Johns River and its tributaries. These undeveloped areas safely store floodwaters, protect communities, and sustain the natural systems that recharge Florida’s aquifer and support wildlife.

In the Middle St. Johns River Basin, the District and Seminole County have acquired more than 8,500 acres of floodplain surrounding Lake Jesup. This allows the expansive lake to naturally fluctuate from about 8,000 to 16,000 acres, depending on rainfall and water levels, providing flood storage and also protecting important wildlife habitat.

In the Upper St. Johns River Basin (Brevard and Indian River counties), wetlands can store an estimated 500,000 acre-feet of water, enough to cover the 200,000-acre project area with 2.5 feet of rain. Similarly, the Upper Ocklawaha River Basin (Orange and Lake counties) can store up to approximately 62,200 acre-feet of water. By protecting and maintaining these natural floodplains, the District allows nature to do what it does best, store and manage floodwaters naturally.

The District continues to expand these protections. In the Lower St. Johns River Basin, 2,722 additional acres of vital floodplain and wetland systems were recently added through the strategic acquisition of the Pablo Creek Conservation Area in Duval County. Protecting these critical wetlands provides non-structural flood protection for the Lower Cedar Swamp Creek watershed, Boggy Branch and Pablo Creek, while also safeguarding water quality and essential wildlife habitat in the lower basin.

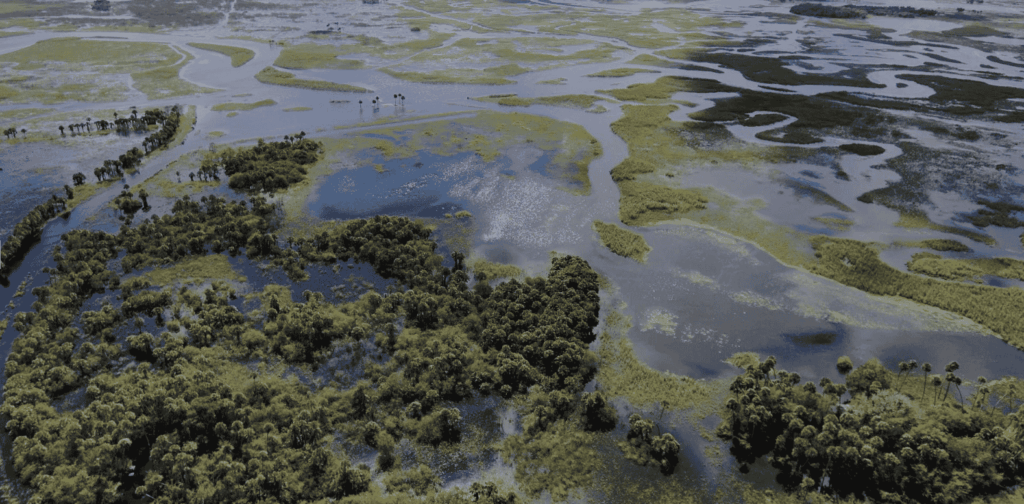

While nature provides powerful flood control benefits, engineered infrastructure also plays a crucial role in managing water levels and protecting communities. In the Upper St. Johns River and Upper Ocklawaha River basins, the District operates spillways, pump stations, levees and canals that allow staff to influence water levels and manage stormwater flows.

Before each hurricane season, engineers lower water levels to increase available storage and reduce flood risk. These managed systems are the only areas where the District directly manages water levels.

Yet the river itself presents unique constraints. The St. Johns flows north for about 310 miles but drops less than 30 feet in elevation from its headwaters to the Atlantic, making it one of the country’s slowest-moving major rivers. Because of its gentle gradient, broad floodplain marshes and multiple tributaries feeding the system, structural controls cannot instantaneously alter water levels across the full stretch of the river

The District’s flood protection network in these two river basins includes 12 major water control structures and spillways, 76 minor water control structures, three navigational locks, one pump station and approximately 115 miles of flood control levees. Many of these systems were developed in partnership with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, beginning after devastating floods in the 1940s. District staff regularly inspect and maintain these structures to ensure they operate effectively when needed most.

This combined natural and structural approach strengthens floodplain storage and helps reduce widespread flooding along the St. Johns River in central Florida. Still, even with these systems in place, extreme or prolonged rain events can exceed what existing lands and infrastructure are designed to manage. This highlights the critical need for continued investment in land acquisition, which expands floodplain storage, helps protect vulnerable areas and enhances the region’s long-term resilience.

To learn more about the District’s work in flood protection, please visit sjrwmd.com/localgovernments/flooding.

Danielle FitzPatrick is a Public Communications Coordinator at the St. Johns River Water Management District