BY LORI COOLIDGE, P.G.

Senior Professional Geologist,

Associate with GHD

Funny how the definition of a word can be viewed so differently by people.

Take the word “adjacent.” Merriam-Webster’s Dictionary defines the word “adjacent” as “not distant: nearby,” “having a common endpoint or border,” or “immediately preceding or following.”

When viewing the word “adjacent” from the regulatory purview of defining wetlands, the waters remain muddied (no pun intended), as do many other aspects of determining what waterbodies are subject to Federal jurisdiction.

The Clean Water Act (“CWA”), promulgated as the Federal Water Pollution Control Act in 1948 and amended and enacted by Congress in 1972, “establishes the basic structure for regulating discharges of pollutants into the waters of the United States and regulating quality standards for surface waters” (US EPA).

The CWA provided the framework for a permitting program to monitor discharges from point sources of pollution to “navigable waters.”

The CWA is the regulatory driver for dredge and fill permits, National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (“NPDES”) permits, water quality standards and the assignment of Total Maximum Daily Loads (“TMDLs”), State and Tribal water quality certification programs, and Spill Prevention, Control, and Countermeasure (“SPCC”) plans.

While the Clean Water Act intended to protect “navigable waters,” the Act defines “navigable waters” only as “the waters of the United States, including the territorial seas.”

It was clear that additional guidance pertaining to the definition of “waters of the United States” (“WOTUS”) was needed. In 1980, the United States Environmental Protection Agency (“EPA”) developed a Rule to define WOTUS, which was adopted by the United States Army Corps of Engineers (“USACE”) in 1982. According to the 1980 rule, WOTUS was defined as:

(a) All waters which are currently used, were used in the past, or maybe susceptible to use in interstate or foreign commerce, including all waters which are subject to the ebb and flow of the tide;

(b) All interstate waters, including interstate “wetlands;.”

(c) All other waters such as intrastate lakes, rivers, streams (including intermittent streams), mudflats, sandflats, “wetlands,” sloughs, prairie potholes, wet meadows, playa lakes, or natural ponds the use, degradation, or destruction of which would affect or could affect interstate or foreign commerce including any such waters:

(1) Which are or could be used by interstate or foreign travelers for recreational or other purposes;

(2) From which fish or shellfish are or could be taken and sold in interstate or foreign commerce; or

(3) Which are used or could be used for industrial purposes by industries in interstate commerce;

(d) All impoundments of waters otherwise defined as waters of the United States under this definition;

(e) Tributaries of waters identified in paragraphs (1) – (4) of this definition;

(f) The territorial sea; and

(g) “Wetlands” adjacent to waters (other than waters that are themselves wetlands) identified in paragraphs (a) – (f) of this definition.

Although the 1980 definition provided clarity in some regards, additional clarification, particularly relating to waterbodies located within a state but impacting cross-state waters, was needed.

Litigation ensued, and in a 1985 Supreme Court ruling in the United States v. Riverside Bayview , the court ruled that the CWA could be applied to intrastate wetlands after a developer began placing fill material without a dredge and fill exception near Lake St. Clair, Michigan.

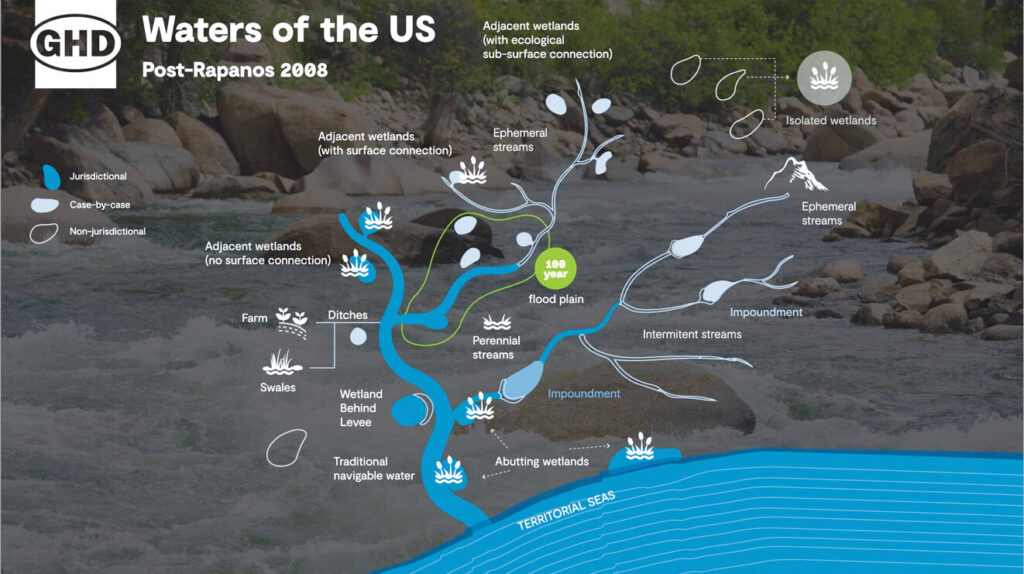

However, as determined in subsequent Supreme Court proceedings in Rapanos v. U.S., 547 U.S. 715 (2006), a narrower definition of WOTUS and what “waters” fell under Federal jurisdiction was sought.

In the case, the court considered whether three wetlands fell under the purview of the CWA. Based on the proceedings, two alternative methods were proposed for determining if “water” was jurisdictional under the CWA.

Justice Scalia suggested that the term “water” was defined as only being “relatively permanent, standing or continuously flowing bodies of water,” thereby eliminating ephemeral or intermittent waterbodies.

In addition, only wetlands that had “continuous surface connection” to WOTUS were considered jurisdictional.

Conversely, Justice Kennedy provided a method that would determine jurisdiction on a case-by-case basis, which would be applied if the presence of a “significant nexus” had been established to a WOTUS.

It was further noted that a “significant nexus” was confirmed if a wetland significantly impacted the “chemical, physical, and biological integrity” of a WOTUS. This eliminated the necessity for a continuous surface connection and introduced jurisdiction over wetlands ecologically connected to a WOTUS.

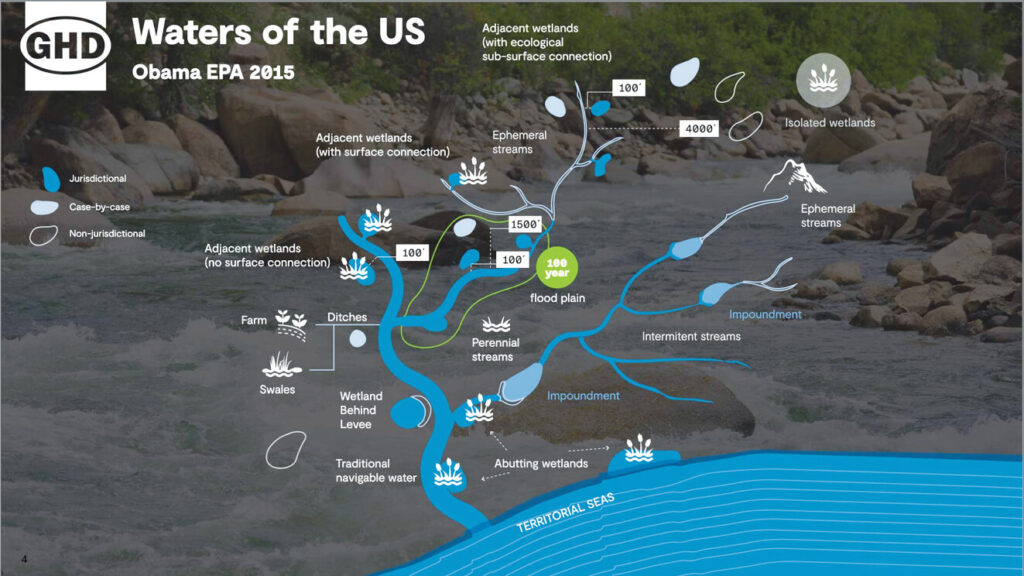

The Clean Water Rule of 2015 sought to clarify what waters were protected under the CWA further. An EPA Fact Sheet was released to detail the changes to WOTUS with a more defined scope to reduce the case-by-case analysis of water bodies to determine jurisdiction.

Tributaries were required to show the physical features of flowing water to fall under CWA protection. Under the Rule, boundaries were set for nearby waters that were both “physical and measurable.”

Specifically, adjacent waters and wetlands included as WOTUS were defined as “waters adjacent to jurisdictional waters within a minimum of 100 feet and within the 100-year floodplain to a maximum of 1,500 feet of the ordinary highwater mark.”

Also included in WOTUS were “waters with a significant nexus within the 100-year floodplain of a traditional navigable water, interstate water, or the territorial seas, as well as waters with a significant nexus within 4,000 feet of jurisdictional waters.”

As with preceding rules, the definition of WOTUS was scrutinized, with some opposing groups citing the regulation as being overreaching, and “stretching” the meaning of the word adjacent.

As a result, litigation successfully blocked the Rule with court-ordered injunctions in several states. In these states, the 1986/1988 rule was reinstated.

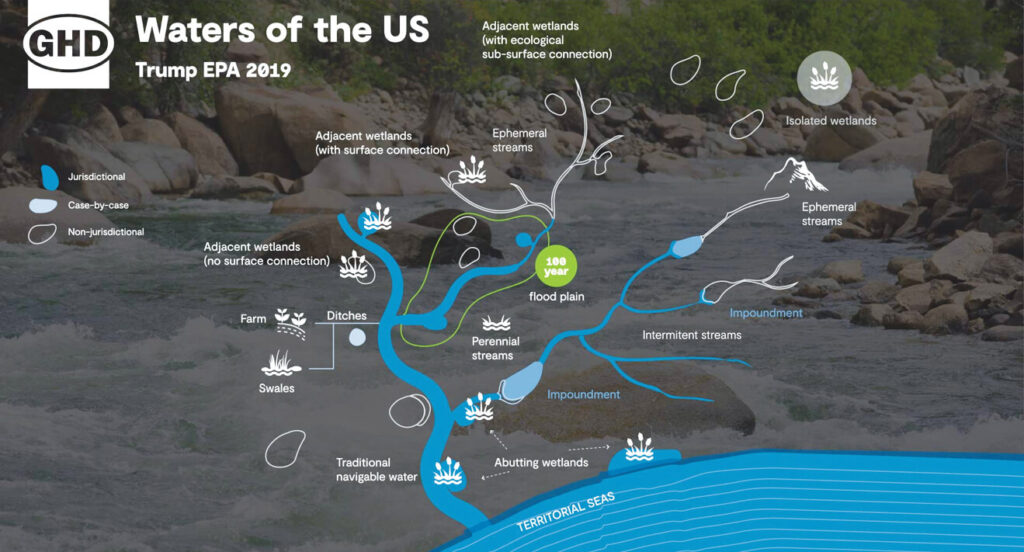

An Executive Order issued by the Trump Administration in 2017 directed the EPA and the USACE to consider utilizing the test for determining WOTUS as opined by Justice Scalia in Rapanos v. the U.S.

In 2020 the definition of WOTUS was changed once again, which reduced the number of wetlands under jurisdiction by eliminating those that were not directly adjacent or having a direct hydrological surface connection to a WOTUS.

Known as the Navigable Waters Protection Rule (“NWPR”), waters were divided into two broad classes, Jurisdictional and Non-Jurisdictional.

Under NWPR, circumstances during a “typical year,” as defined in the Rule as “when precipitation and other climatic variables are within the normal periodic range for the geographic area … based on a rolling 30-year period,” are evaluated to determine if the water body met the jurisdictional definition.

The Rule also created 12 categories of WOTUS exclusions that included most wetlands, isolated water bodies, and ephemeral and intermittent streams. Court proceedings against the NWPR resulted in the Aug. 30, 2021, ruling wherein the U.S. District Court for the District of Arizona ruled that the Rule was “too flawed” to keep in place, and as a result, the EPA and USACE announced that the Pre-2015 regulatory definition of WOTUS would be reinstated.

The August 2021 ruling and the subsequent announcement by the EPA and USACE ignited some controversy in the State of Florida.

Before the ruling, Florida became the third state to be granted authority from the EPA to oversee wetlands permitting. Following the verdict, Florida determined that it would continue to follow the NWPR while discussions regarding the vacatur of the Rule continued.

The EPA disputed this determination and maintained that the power to veto delegated authority for permitting. In the end, the controversy was squashed when the Supreme Court put a hold on the vacatur of the NWPR until a new rule was adopted.

The EPA released the “Revised Definition of ‘Waters of the United States’” Rule on Dec. 30, 2022, which will be effective 60 days after it is published in the Federal Register.

In the Executive Summary of the Proposed Rule, the issue with WOTUS is clearly explained, “[t]he transitions from water to solid ground is not necessarily or even typically an abrupt one. Rather, between open waters and dry land may lie shallows, marshes, mudflats, swamps, bogs — in short, a huge array of areas that are not wholly aquatic but nevertheless fall far short of being dry land.”

Jurisdiction for tributaries, adjacent wetlands, and additional waters under the new Rule is determined by the “significant nexus standard” and “relatively permanent standard” tests.

The new Rule also provides a list of eight exclusions from WOTUS. However, based on the lack of additional clarification on the definition of significant nexus, and the necessity of professional judgment to determine if significant nexus applies, it is inevitable that this Rule too will be met with questions and scrutiny.

To further complicate issues, the Rule was released prior to the decision in the on-going Supreme Court case Sackett v. EPA, which is squarely focused on the legality of the significant nexus test. With over 1,000 dredge and fill permits already filed in 2022 in the State of Florida, changes to the definition of WOTUS can cause denials, delays, and possibly additional costs on development projects. It is unclear if the definition of what an “adjacent” waterbody is will ever be agreed upon.●

Lori Coolidge is a Senior Professional Geologist and Associate with GHD in Tampa, Florida. She specializes in due diligence assessment, environmental permitting, contamination assessment, and surface water quality projects.