By LINA ALFIERI STERN

Within two weeks in late September and early October 2024, hurricanes Helene and Milton wreaked havoc across Florida, leaving significant environmental and infrastructural challenges in their wake. As efforts continue to recover from the wind and flooding damage these storms brought, the full environmental impact is not yet known.

Hurricane Helene made landfall on Sept. 26, followed by Hurricane Milton on Oct. 9. Highlighting the severity of their effects, Hurricane Milton alone knocked out power for more than 3 million customers and triggered around 150 tornado warnings. The Atlantic hurricane season runs from June 1 to Nov. 30.

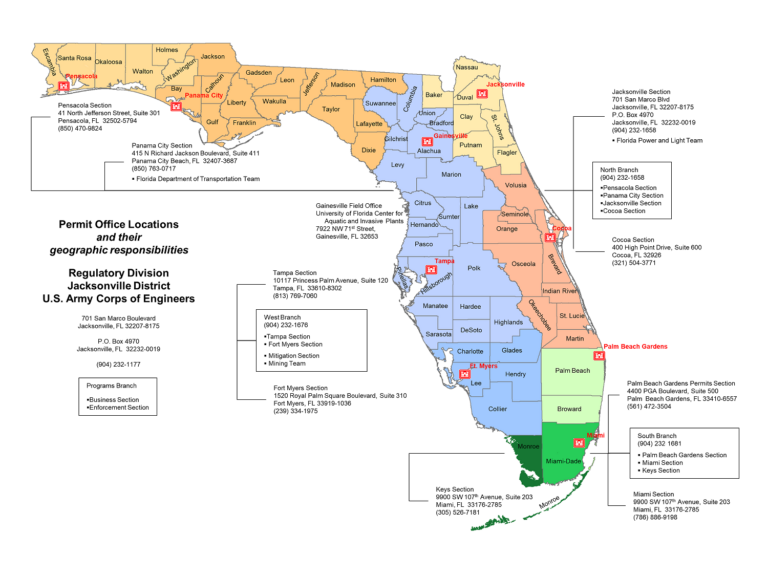

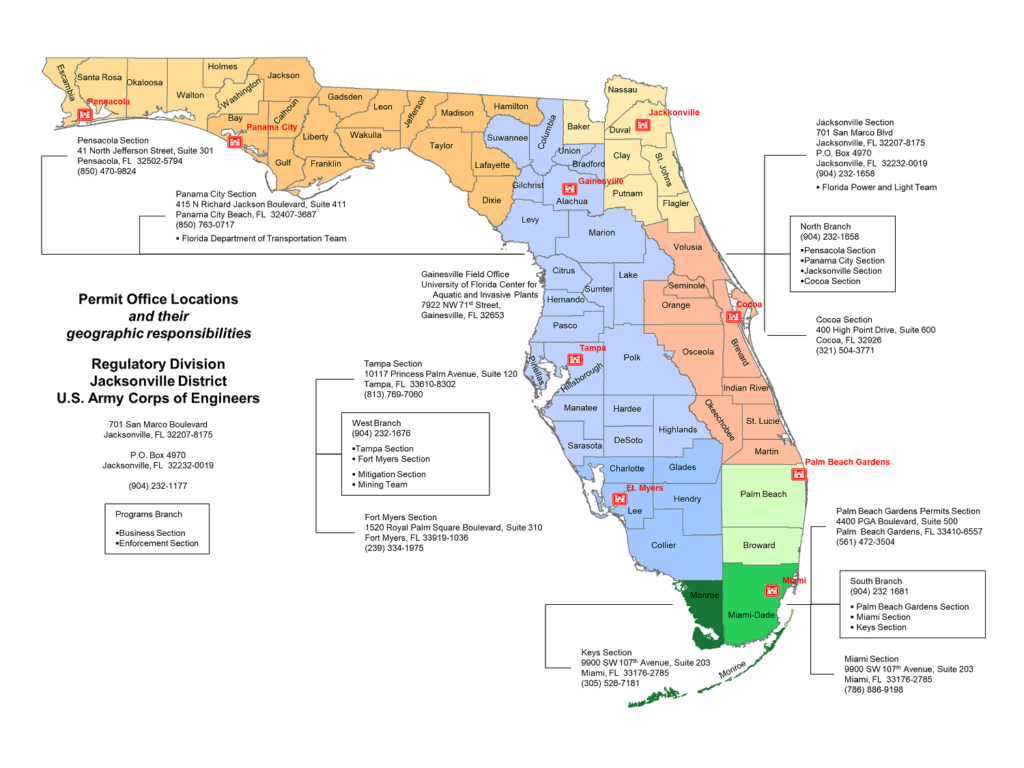

The storms did not just disrupt everyday life; they also exposed vulnerabilities within critical infrastructure. From Tampa to St. Petersburg to Lakeland, dozens of municipal wastewater systems in the path of the hurricanes failed, spilling millions of gallons of wastewater into public waterways. According to Rice University’s Center for Coastal Futures and Adaptive Resilience Toxic Release Inventory (TRI), there were 2,200 TRI facilities in Helene’s cone of impact and 694 in Milton’s, which represent facilities that process more than 142 million and 26 million pounds, respectively, of hazardous materials per year.

Tampa reported discharging 8.5 million gallons of sewage from ten overflows, all along the Hillsborough River and the south Tampa coastline, according to news reports.

Flooding in the Apollo Beach and Ruskin communities caused damage to wastewater pumping systems in south Hillsborough County. Backup generators limited the damage that would have been caused by loss of power, but some pumps were damaged due to electrical shortages.

St. Petersburg’s overwhelmed infrastructure during Hurricane Helene resulted in the discharge of nearly 1.5 million gallons of untreated wastewater throughout the area, according to the Tampa Bay Times. Approximately two-thirds of this pollution originated from the Northeast Water Reclamation Facility, which began leaking on the night of Sept. 26. The facility, which typically processes 8 to 10 million gallons of sewage daily, was offline for at least 48 hours, affecting a quarter of the city’s population. In addition to this major discharge, six other incidents of untreated wastewater occurred in the area, releasing approximately 220,550 gallons into local waterways.

St. Pete Beach City Manager Fran Robustelli reported that the town’s sewer system faced significant challenges during the hurricanes stemming from equipment failures, namely the 21 lift stations that transport wastewater to the treatment plant in St. Petersburg. During Hurricane Helene, storm surges damaged control panels at eight of these stations, rendering them inoperable. Hurricane Milton further aggravated matters by causing utility power loss at all lift stations. Nine lift stations require repairs, with construction expected to take approximately 18 months.

The Lakeland district documented at least eight spills impacting Lake Somerset, Lake Parker, Lake Hollingsworth, Lake Bonny, Lake Bentley, and the Lake Hunter Outfall Ditch. The two most significant spills occurred at the Glendale Wastewater Reclamation Facility in southeast Lakeland, which has been in operation since 1926, and together accounted for five million gallons, according to reports filed to the Florida Department of Environmental Protection.

Little is yet known about the full environmental consequences of the hurricanes on industrial facilities. Hurricane Helene’s storm surge flooded the retired Crystal River nuclear power plant operated by Duke Energy. Rising waters inundated the site, including its buildings and wastewater facilities, raising concerns about low-level radioactive waste and the potential impact of flooding, especially in light of a similar incident after Hurricane Idalia in 2023. While Duke Energy reassured the public that used nuclear fuel is securely contained, the facility is set to hold spent fuel until 2037.

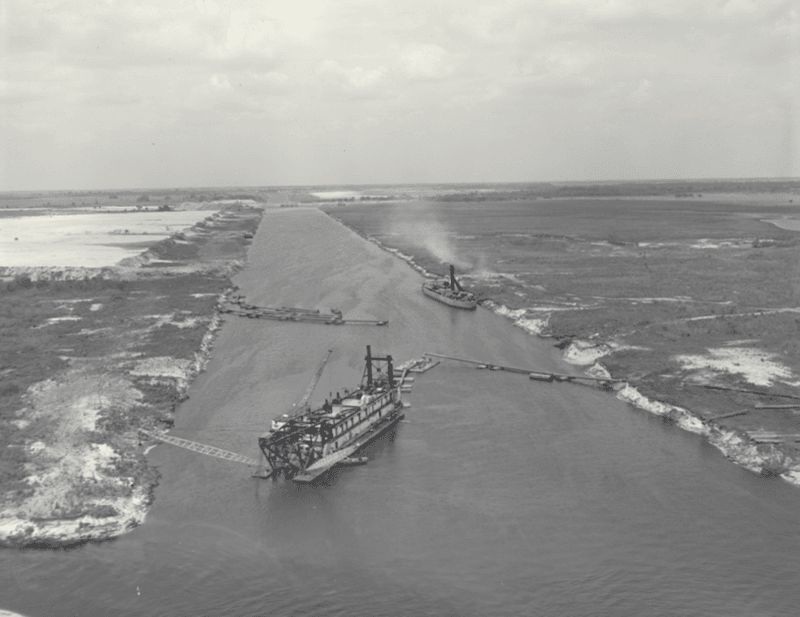

The Mosaic Company reported a pollution spill into Tampa Bay during Hurricane Milton. Heavy rainfall overwhelmed the company’s collection system at its Riverview phosphate mine, leading to an escape of excess water through a manhole. The leak exceeded the 17,500-gallon minimum reporting threshold, although the company did not specify the exact volume. Florida is home to 25 phosphogypsum plants, which together house more than 1 billion tons of a solid waste byproduct from phosphate fertilizer mining. This byproduct contains radium, which decays into radon gas, and is associated with cancer risks.

While organizations such as Rice University’s Center for Coast Future’s and Adaptive Resilience (CFAR) track the locations of industrial facilities in the path of hurricanes (see CFAR Interactive Map), they are unable to get real-time data on the impact of natural disasters and other disruptive events to those facilities.

“Companies do not always disclose spill data,” said CFAR’s Co-Director Dr. Dominic Boyer. “Our tool helps to make risks more visible, but we don’t have a way yet of tracking damages.”

Many facilities are not required to disclose their risks, and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) mandates only general details in risk management plans, which can be difficult for the public to access. Furthermore, many states, including those along the Gulf Coast, often relax pollution restrictions during emergencies, and notifications of chemical incidents are frequently delayed.

As Florida grapples with the aftermath of hurricanes Helene and Milton, the intersection of severe weather, environmental safety, and infrastructural integrity remains a pressing concern. Understanding the full impact of these storms on sensitive sites and communities will be crucial for future preparedness and resilience efforts.