By JEFF LITTLEJOHN

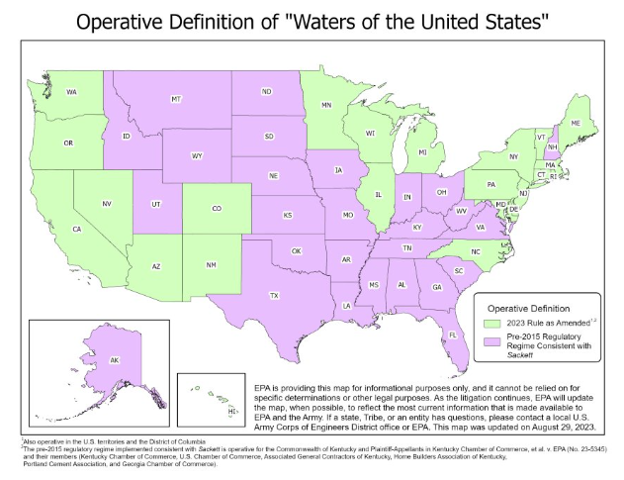

Every White House for the past 20 years has tried to create its own definition of Waters of the United States, or WOTUS, and each of these attempts has been challenged in the courts. The result is a patchwork of regulation, based on the state. To illustrate, 23 states are regulated under a WOTUS rule that took effect in March 2023, called the “2023 Rule.”

The other 27 states, including Florida, have their federal wetlands defined under a “pre-2015 regulatory regime.” These 27 states were parties to one of three separate cases, which resulted in each of these federal courts striking down the 2023 Rule in March, April, and May of 2023. Then, in May 2023, the Supreme County issued a landmark opinion that required major revisions to both definitions.

And now, the latest twist in this saga involves a recent case filed in North Carolina, “White v. EPA,” which threatens to upend the already complex situation imposed by the courts.

The ill-fated 2023 Rule, dubbed the “Final Revised Definition of Waters of the United States,” faced a swift demise, with one federal court striking it down even before it went into effect, and other court decisions vacating it across most of the country. The Supreme Court’s 2023 decision in “Sackett v. EPA” further undercut the rule’s validity, rendering it in conflict with important provisions of Sackett. In response, federal agencies quickly issued a “Conforming Rule,” attempting to align with the Court’s ruling.

White challenges the validity of the Conforming Rule. Attorneys representing the plaintiffs argue that the rule’s expansive definition of jurisdictional wetlands contradicts the clear directives outlined in Sackett. They further contend that the amended definition encroaches on due process rights, and the Rule blurs the line between federal and state authority.

Indeed, the battle over WOTUS appears to have been extended beyond legal technicalities to more fundamental questions of federalism and the constitutional powers granted to Congress. Critics argue that an overly broad interpretation of federal jurisdiction undermines the rights and autonomy of states to regulate water resources within their boundaries. The situation is so complex that EPA has a dedicated website with a map “to illustrate which definition of [WOTUS] is generally operative in each state across the country… As the litigation continues, EPA will update the map, when possible, to reflect the most current information that is made available to the EPA and the Army.”

When the Sackett decision was handed down in May 2023, the Court issued clear guidance to the federal agencies that their jurisdiction “extends only to the limits of Congress’ traditional jurisdiction over navigable waters.” The simplified WOTUS definition in Sackett includes only: traditional, navigable waters such as “streams, oceans, rivers, and lakes” and wetlands when they are continuously connected to, and indistinguishable from, navigable waters. The Conforming Rule was issued, according to the federal agencies, to comply with the Court’s instructions.

However, the same attorneys that represented Sackett are representing White, and observers believe “White” may result in the invalidation of the Conforming Rule.

The trouble with the Conforming Rule, according to the complaint, is that the agencies defined all wetlands with a continuous surface connection to navigable waters as jurisdictional. Without mentioning “indistinguishable” in their latest definition, a “continuous enough” test becomes a means of expanding jurisdiction through one or more non-jurisdictional features to reach wetlands far away from a navigable water. To illustrate, artificial conveyances like ditches and pipes can create continuous surface connections that extend miles from navigable waters. This is contradictory to Sackett’s bottom line: jurisdictional wetlands must “be indistinguishably part of a body of water that itself constitutes ‘waters’ under the CWA” and “[w]etlands that are separate from traditional navigable waters cannot be considered part of those waters, even if they are located nearby.”

According to White, the “Conforming Rule” conflicts with another provision of Sackett – that agency jurisdiction must be clear and predictable:

The Agencies contend that they may ascertain a “continuous surface connection” in numerous ways that cannot be readily discerned by the regulated public, 88 Fed. Reg. at 3093–95—thus reaching all manner of land-use activities that one could not possibly know are subject to the Agencies’ authority. Such an interpretation cannot be sustained. Cf. Sackett, 598 U.S. at 680–81 (“Due process requires Congress to define penal statutes ‘with sufficient definiteness that ordinary people can understand what conduct is prohibited’ and ‘in a manner that does not encourage arbitrary and discriminatory enforcement.’”)

In other words, according to Sackett, fact-intensive, case-by-case jurisdictional determinations that require expertise beyond that of ‘ordinary people’ violates due process rights granted by the U.S. Constitution and would require powers beyond even the authority of Congress to grant.

Finally, the White case restates concerns raised in Sackett about the division of authority between Congress and the States. Restated from Sackett, “the Clean Water Act expressly ‘protect[s] the primary responsibilities and rights of States to prevent, reduce, and eliminate pollution’ and ‘to plan the development and use … of land and water resources.’ It is hard to see how the States’ role in regulating water resources would remain “primary” if the EPA had jurisdiction over anything defined by the presence of water.” For states like Florida, with comprehensive wetland protections afforded as far back as 1984 with the passage of the Warren S. Henderson Wetlands Protection Act, regulatory jurisdiction exists for all wetlands, without distinction between navigable waters and other waters of the state. Simply put, all waters and wetlands in Florida benefit from state regulatory protections. Yet, the federal regulatory quagmire continues to complicate the wetland protection regime, leaving applicants caught in regulatory limbo.