By BLANCHE HARDY

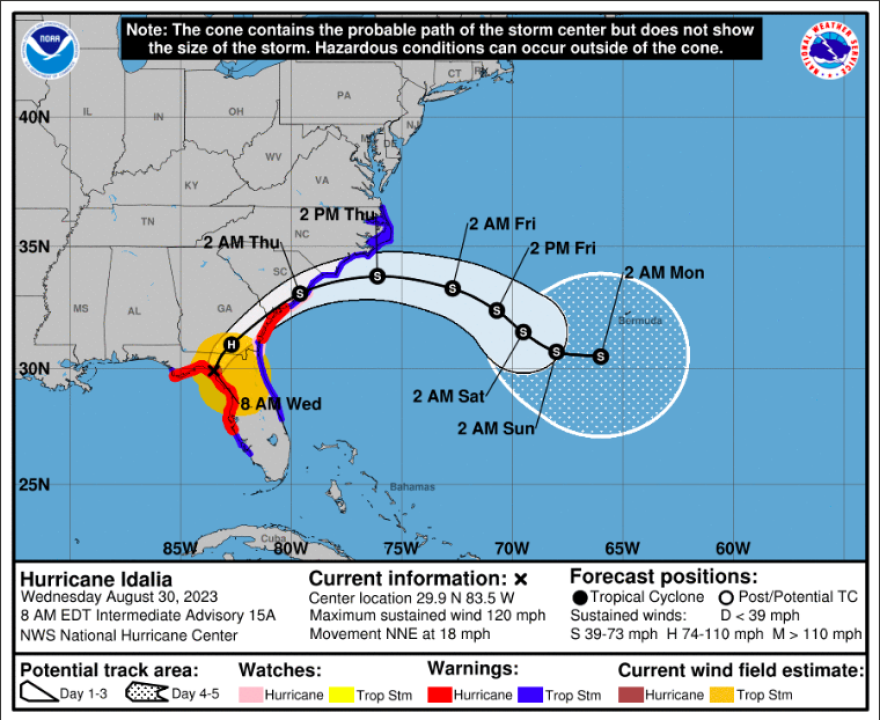

By this point, it seems like a long time since Hurricane Idalia attained Category 4 strength before making landfall on August 30 as a robust Category 3 hurricane in Florida’s Big Bend.

Idalia came ashore at Keaton Beach, a few miles south of Perry, and while the news coverage faded after a while, the impact of Hurricane Idalia continues to have an effect on the state of Florida and will for some time.

While attention is frequently given to structure and infrastructure property damage, impacts occur well beyond the built environment in both natural ecosystems and on cultivated lands. For Idalia, the University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences (IFAS) projections indicate losses could reach between $79 million and $380 million, according to a Septemberreport titled, “Preliminary Assessment of Agricultural Losses and Damages Resulting from Hurricane Idalia.”

Meanwhile, Wilton Simpson, Commissioner of the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, told a Florida House committee in October that his agency is estimating agricultural losses from Idalia reached $500 million. He is seeking funding to assist in helping farmers recover.

To gauge agrarian impacts, IFAS is conducting a preliminary assessment of the agricultural losses and damages resulting from Hurricane Idalia. IFAS estimates agricultural lands affected by Hurricane Idalia typically produce over $3.9 billion in agricultural products (crops, livestock, aquaculture, etc.) throughout a calendar or marketing year.

IFAS found the commodity groups that were most affected in terms of value by Idalia’s hurricane conditions include animals and animal products, field and row crops, and vegetables and melons. IFAS notes that producers can experience losses by different means, such as unfavorable changes in the level or value of commodity sales, changes in input costs, and losses resulting from damages requiring repair or replacement. Agricultural losses may result in a variety of ways and combinations.

The IFAS report projects that at a Category 3, the high-loss scenario is — up to 55 percent of citrus, 50 percent of field and row crops, 70 percent of fruit and nut tree yields, 25 percent of animal and animal products, and 35 percent of vegetables and melons might be lost as a result of Idalia.

The assessment indicates damage may result from wind-damaged field and row crops, crop losses due to high winds in a pecan grove, water quality or mortality issues for shellfish aquaculture operations, lower milk production at a dairy farm due to stressed cattle or the need to dump milk due to issues with cold storage during a power outage, or even a lower sales price for a beef cattle rancher that had cattle that were not able to get the appropriate nutrition due to stressor damaged grazing lands.

IFAS researchers are also considering losses to agricultural assets such as fencing, irrigationsystems, farm homes, farm buildings, greenhouse and nursery structures, machinery/equipment, other infrastructure, livestock animals, and perennial plantings such as pecan or citrus trees and vineyards.

The preliminary assessment report indicates more than 3.3 million acres of Florida’s agricultural lands were affected by Idalia, and roughly 74 percent was grazing land. The commodity group acreage that was most affected were animals and animal products and field and row crops.

Florida has implemented a cost-sharing program to support impacted growers through the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services’ Office of Agricultural Water Policy and will support agricultural producers in repairing or replacing damaged irrigation systems, while simultaneously promoting agricultural water efficiency and reducing nutrient application.

“Hurricane Idalia caused widespread crop and livestock losses and severe damage to agricultural infrastructure,” said Simpson. “This innovative cost-share program will work to support our hardest hit growers who lost much of their 2023 crop and are now looking for ways to repair or replace hundreds of irrigation systems ahead of the next growing season.”

Thomas Miller, Biological Sciences Professor at Florida State University, said there are many natural effects that persist post-storm.

“Barrier Islands occur on some 80 percent of the coastlines of Florida (and the rest of the Northern Gulf of Mexico) and serve as a first defense from hurricanes,” he said. “They can take the brunt of winds, waves, and storm surge, protecting not only homes and towns, but seagrass beds, oyster beds, and saltmarshes. Hurricanes often destroy foredunes on these islands, making inland areas more susceptible to later storms. Mitigation varies from site to site. In some places, artificial foredunes are bulldozed back in place and planted with key plant species, such as seaoats. In other places, shores are fortified with wind fences, rock, or beach renourishment.”

Some preparation can be made, but not everything can be fortified. Even birds were thrown off course by Idalia, as some flamingos typically confined to central Florida and south were spotted as far north as Ohio and Pennsylvania.

“What we do need is better long-term monitoring to understand how storms affect coastal dunes and to determine the effectiveness of different damage mitigation after storms,” Miller said. “If storms are increasing in frequency or intensity, we can also predict mitigation needs after storms.” ●