By FRED MAYS

Mangroves are among the most abundant trees on the planet, covering temperate and tropical inter-tidal shorelines around the world. Sadly, and most-notably here in Florida, as development sprawls in coastal areas, mangroves have disappeared at an alarming rate.

Mangroves once occupied millions of acres of Florida’s waterways. Given the coastal development of the past 50+ years, today’s estimate of mangroves is less than 470,000 acres, according to the Florida Department of Environmental Protection (FDEP).

Along the banks of the Indian River Lagoon and along Florida’s east coast, for example, it is estimated almost 70% of the mangroves are gone, lost to development.

Mangroves are halophytes, plants that can live in saline water. They play an important role in our environment as they are a strong “carbon sink,” trapping atmospheric carbon dioxide at a rate 10 times more effective than land-based trees. Mangroves provide protection to shorelines from erosion as well as habitats for marine life.

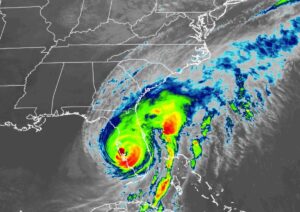

Mangroves played a role during Hurricane Ian this summer, according to University of Florida expert David Outerbridge. “I saw areas fared better with mangroves protecting the shoreline. The north end of Pine Island, in particular, was spared because of mangrove protection. Some mangrove areas were damaged during Ian, but are already bouncing back, day by day getting better. They are very resilient.”

Mangrove studies on Florida’s east coast, from Hurricane Nicole, are just getting started.

Around the world there are dozens of varieties of mangroves. In Florida there are three . . . Red mangroves (Rhizophora Mangle), White mangroves (Laguncularia Racemusa), and Black mangroves (Avelennia Germinans). Each has a role to play along shorelines.

Red mangroves are found at the mean tidal waterline, their roots surviving in the salty water. Reds drop seedpods year-round, and propagate quickly. growing nearly five feet in a year. As their long roots grow, they become habitat for oysters, small fish, and even young sharks.

White mangroves are found just behind the Reds, filling in the shoreline. The Reds and Whites offer a stabilizing environment, reduce erosion, and fill in sand along the intertidal area. It is not uncommon for shorelines to grow 10-20 feet when lined with mangroves.

Black mangroves are farthest back from the water line. They have larger trunks, and their leaves secrete salt to rid the tree of the saline water. Blacks are the tallest of the mangroves, sometimes reaching 15-20 feet high. Their wood has been used as a building material.

After decades of developers ripping out mangroves, today in Florida it is illegal to cut down mangroves without a permit. Although mangroves form a natural and effective barrier against shoreline erosion, many property owners tear them out and replace them with seawalls and large boulder “rip rap” barriers.

Removing mangroves can be a costly mistake. During Hurricane Irma in 2017, an estimated $1.3 billion in property damage was averted by mangroves, according to a study by the University of California, Santa Cruz. Seawalls can often be topped and breached by pounding storm surge, causing them to lean and eventually collapse. Studies have shown mangrove shorelines are more effective than seawalls in preventing damage from storm surges.

Around the world there are mangrove replanting efforts, designed to counter rising seas. Millions of acres of mangroves have been replanted in Indonesia, Malaysia and throughout southeast Asia. Replanting in Florida is less ambitious. The University of Central Florida has planted over four kilometers of shoreline in the Mosquito Lagoon, near NASA’s Kennedy Space Center.

According to Dr. Melinda Donnelly, Assistant Resource Professor, the UCF project has been ongoing since 2011. It is one of many smaller private restoration projects underway in Central Florida’s lagoons and bays.

The State of Florida does not have public mangrove projects, although some state grants are provided to universities and NGOs (non-government organizations).

According to Dr. Donnelly, the majority of Florida mangrove loss in the last 30 years has been “due to human activities.” But not all of it. Mangroves thrive in the temperate and tropical zones, but are intolerant to cold weather. A series of hard freezes in the 1980’s had a hand in destroying much of the mangroves in Central Florida.

Donnelly says some “large scale” mangrove restoration has occurred in the last 20 years. By all measures it is hard work. Some restoration projects report less than a 50% success rate. Donnelly’s group, however, has devised a replanting process that yields a much higher rate of success.

The shoreline is first protected by several feet of bagged oyster shells to buffer wave action. Behind the oysters are wetland grasses (Spartina Alterniflora), which further protect the intertidal area. Mangroves are then planted behind the grasses in different rows. First the reds, then the whites, and finally the blacks. Donnelly says their success rate is 85% or higher.

Another mangrove project leader, Dr. Caity Savoia of the Marine Resource Council, reports breakwater efforts “work really well” in the replanting process. “Some sites had zero percent success rates,” but behind the breakwaters the rate has been up to 100%. She laments “not having enough natural shorelines left” to replant due to development in coastal areas. She estimates 65% of the natural shoreline in Florida’s Indian River Lagoon has been lost behind seawalls and hardened shorelines.

When people think of trees in Florida, palm trees usually come to mind; but it is the mangrove that is most important to the environment.●

Did you know?

Mangroves once occupied millions of acres of Florida’s waterways. Given the coastal development of the past 50+ years, today’s estimate of mangroves is less than 470,000 acres, according to the Florida Department of Environmental Protection (FDEP). Removing mangroves can be costly. During Hurricane Irma in 2017, an estimated $1.3 billion in property damage was averted by mangroves, according to a study by the University of California, Santa Cruz.